A Lioness? Why Aslan’s Mane Is Important to ‘Narnia’ | Opinion

Opinion by Icarus

The following opinion piece has been adapted from a thread on the NarniaWeb Discussion Forum and features inputs from multiple forum contributors.

Lucy buried her head in his mane to hide from his face. But there must have been magic in his mane. She could feel lion-strength going into her.

Prince Caspian (Chapter 11)

With the recent news that three-time Academy Award winning actress Meryl Streep is in talks to play Aslan in Greta Gerwig’s upcoming adaptation of the Magician’s Nephew, it raises the possibility that Aslan will, for the first time in any filmed adaptation, be portrayed as a female Lioness, rather than a male Lion.

A switch of this nature therefore raises numerous potential implications for any future Narnia adaptations in the series, due to the fact that female Lions, unlike male Lions, do not have manes.

Female lions apparently can, in certain exceptionally rare circumstances grow manes in nature, but in general, Lions are one of many creatures where the males and the females of the species look significantly different from one another.

Below we discuss some of the key impacts that a mane-less Aslan could have for the series.

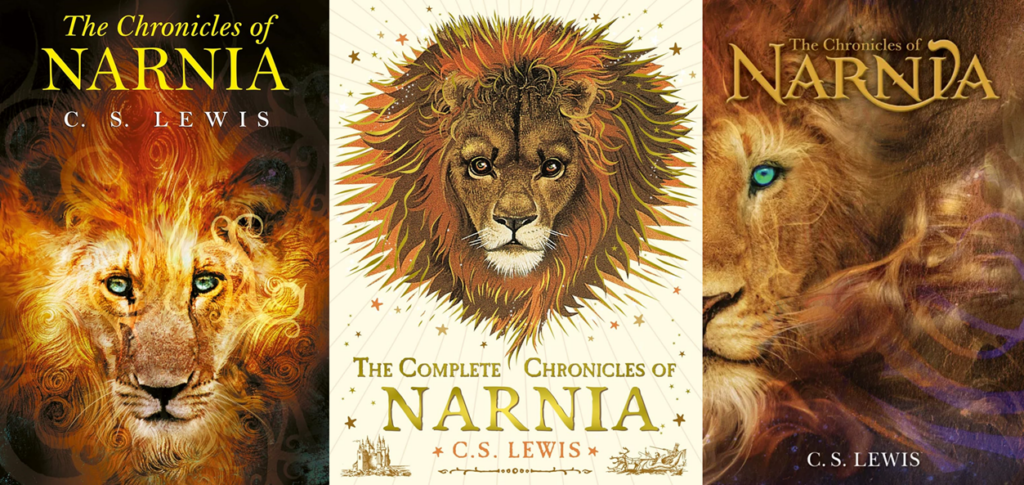

Iconography

First and foremost, the image of Aslan with his radiant mane, is perhaps one of the most iconic and enduring pieces of visual imagery, not just within the Chronicles of Narnia itself, but also within children’s literature as a whole.

It is quite literally the cover image for the majority of the Narnia collected edition books, and in terms of wider popular culture, it is probably up there alongside the Wardrobe and the Lamppost as one of the single most quintessentially Narnian visuals.

It is difficult therefore to fathom what could possible be gained from discarding such a potent and highly marketable symbol, one that for many people is the single most important and defining visual image of the entire series.

The Stone Table

In one of the most pivotal scenes of probably the most important book of the entire series, the villain Jadis, quite literally strips Aslan of his mane, in a powerful and symbolic demonstration of evil triumphing over good.

“Stop!” said the Witch. “Let him first be shaved.” Another roar of mean laughter went up from her followers as an ogre with a pair of shears came forward and squatted down by Aslan’s head. Snip-snip-snip went the shears and masses of curling gold began to fall to the ground. Then the ogre stood back and the children, watching from their hiding-place, could see the face of Aslan looking all small and different without its mane. The enemies also saw the difference.”

The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe (Chapter 14)

There is of course a certain irony in the director of any Narnia adaptation coming to embody the actions of its primary villain by quite literally depriving Aslan of his mane, but there are also significant cinematic ramifications as well.

In a visual medium such as film, the symbolic act of shaving Aslan’s mane allows you to convey so much information to the audience with such a simple and striking visual moment. The Walden films in particular really leaned into the iconography of this moment by having the White Witch subsequently wear Aslan’s discarded mane into battle.

The Prophecy

In a less pivotal, but still no less memorable part of the book, Mr Beaver recites the words of prophecy to the children, which had been passed down between generations of Narnians, and which sets into motion the events of the story:

Wrong will be right, when Aslan comes in sight,

The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe (Chapter 8)

At the sound of his roar, sorrows will be no more,

When he bares his teeth, winter meets its death,

And when he shakes his mane, we shall have spring again

This is again something which the Walden movies actively leaned into with their production design, by having the final line of the prophecy engraved down one side of Peter’s sword, Rhindon.

Whilst it may be easy enough for a good writer to work around this issue, it is none-the-less a frustratingly unnecessary change caused by any switch from Lion to Lioness.

Riding on Aslan’s Back

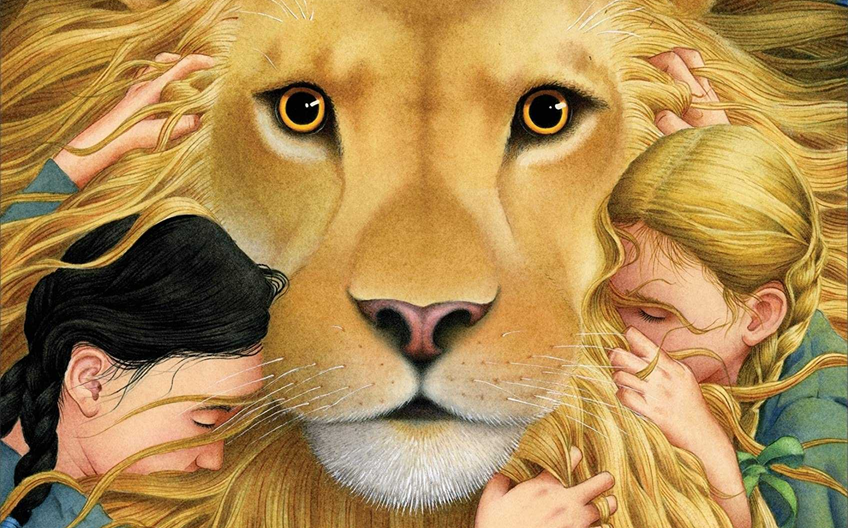

Another hugely iconic scene from ‘The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe’ features Lucy and Susan holding onto Aslan’s mane as they ride on his back to join the battle following Aslan’s dramatic resurrection.

Not only does this image feature on numerous book covers, and stage play posters, but it also features as the cover illustration for the very first published edition of ‘The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe’ from 1950.

Whilst it is no doubt theoretically possible to ride on the back of a Lioness without having a mane to hold onto, the lack of one undoubtedly makes it much harder for an audience to suspend their disbelief over the matter, and just makes what is already a visually complex scene ever so slightly more difficult to bring to life on the big screen.

Characters Burying Themselves in Aslan’s Mane

At several key points, across multiple stories, there are fairly crucial scenes in which the characters bury themselves in Aslan’s mane for comfort.

She felt her heart would burst if she lost a moment. And the next thing she knew was that she was kissing him and putting her arms as far round his neck as she could and burying her face in the beautiful rich silkiness of his mane.

Prince Caspian (Chapter 10)

Further, when Aslan is going to meet the White Witch at the Stone Table, he asks Susan and Lucy to hold on to his mane in the midst of his own despair:

“Aslan! Dear Aslan!” said Lucy, “what is wrong? Can’t you tell us?”

The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe (Chapter 14)

“Are you ill, dear Aslan?” asked Susan.

“No,” said Aslan. “I am sad and lonely. Lay your hands on my mane so that I can feel you are there and let us walk like that.”

As well as the pure symbolism of these moments, they also make for great cinematic visuals which are rich with emotion. By having a mane-less Aslan, you needlessly deprive yourself of these intimate and visually compelling character moments.

Aslan as a Metaphor for the Sun

One of the strongest visual motifs of ‘The Voyage of the Dawn Treader’, and a central argument of Dr Michael Ward’s ‘Planet Narnia’ theory, is the idea of Aslan as a metaphor for the sun.

This visual iconography, which associates Aslan’s golden radiant mane with that of the sun, was even used as the central image on the sail of the Dawn Treader ship in the BBC TV adaptation from 1989.

For such a powerful visual motif, which perfectly encapsulates the notion of sailing East towards Aslan’s Country and the rising sun, removing Aslan’s mane yet again deprives you of another iconic thematic image around which to structure your visual storytelling.

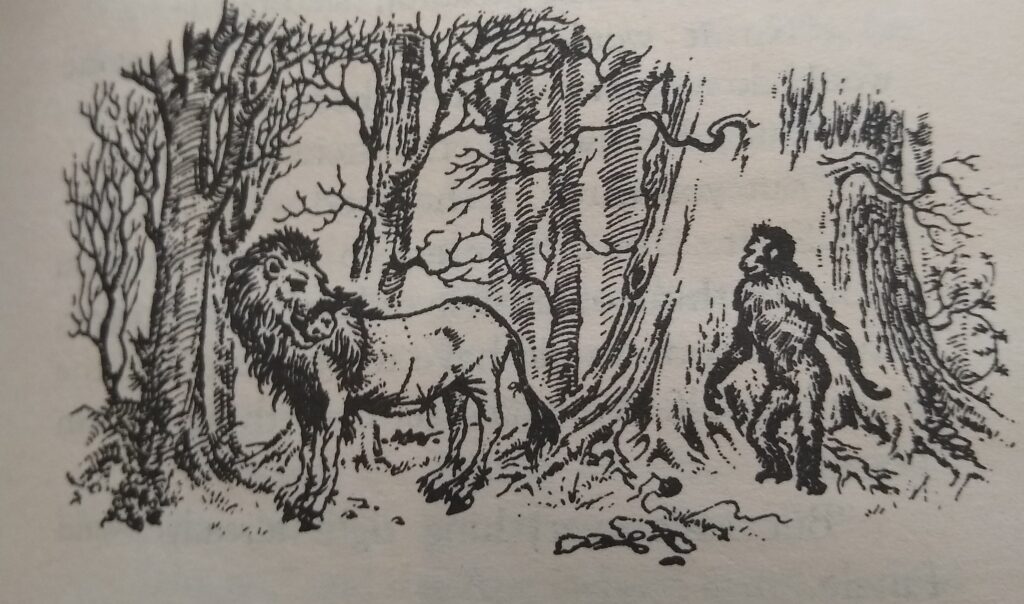

Shift’s Entire Plan in ‘The Last Battle’

Possibly one of the biggest narrative problems which arises from Aslan not having a mane is Shift’s entire plan in The Last Battle. The central conceit of the plot revolves around Shift the Ape finding a Lion’s Skin, complete with mane, floating in the river.

By dressing up his donkey accomplice Puzzle in the Lion’s mane, he manages to convince the creatures of Narnia that he is Aslan, leading to an apocalyptic sequence of events which ends in the destruction of Narnia itself.

Without the transformative effect that the Lion’s mane provides in changing Puzzle’s overall visual profile and appearance, particularly when viewed in silhouette by the dim light of Stable Hill, it is difficult to imagine how Shift could possibly pull off this plan in a universe where Aslan doesn’t even have a mane in the first place.

The idea of merely draping the skin of a Lioness over the frame of a donkey would likely be of insufficient visual impact to set him apart him from any other common four-legged animal.

Even just putting aside the plot mechanics here though, the use of the mane in this story is not just a convenient plot device, but it is also a pivotal thematic symbol of Aslan himself, and a crucial piece of cultural iconography, both to the reader of the book, and to the inhabitants of Narnia within the story.

The Lion as the “King of Beasts”

Perhaps the main reason that C.S. Lewis chose a Lion to represent the most important character in the world of Narnia is the reputation that Lions have as being the “King of Beasts”.

More so than any other big cat or apex predator in the wild, Lions throughout history have been revered as the Kings of the animal world. This is at least in part due to the majestic and regal appearance of a fully-maned Lion, which evokes the idea of golden halo or aura around their face.

It is therefore difficult to imagine the character of Aslan having the same awe-inspiring visual impact as he does without his mane.

Have an idea or topic for a future opinion piece? Head to the NarniaWeb Discussion Forum to share your thoughts!

I completely agree with all of this. If it’s true that Aslan has been changed to a female lion in the upcoming film, it’s deeply troubling that the filmmakers would make the choice to visually distance itself from The Chronicles of Narnia as it has always been known to its fans and the public imagination. It would be hard to look at a decision like that and not think that they were deliberately disassociating from the Narnia canon.

Referring to Aslan as “The Queen of Beasts” would seem out of place. I wouldn’t want to see the Beavers worshipping a lioness. I think if Greta Gerwig wants to satisfy the Narnia fans she will portray Aslan exactly as he is in the story. The people who love the books wouldn’t want it any other way. 🙂

Well said, all of this. It just makes it all the more baffling as to why any film-maker would seriously think a female Aslan is a good move. If this really is being planned — and at this stage, we still don’t have hard evidence that it is, but certainly a disquieting lack of reassurance that it *isn’t* — this article brings out so many reasons why it would change the nature and essence of the stories themselves almost beyond recognition, as well as changing the nature and essence of the particular character. Many thanks to Icarus for compiling and sharing all this.

Thanks for making this into an article, Icarus. Now I can just share it with people instead of having to write my own blog post about how making Aslan a lioness wouldn’t change the plot of The Magician’s Nephew (assuming that’s the first Netflix Narnia movie) but would be an irritating distraction.

Well, I still might write my own blog post but now it can be shorter. (I’ll just include a link to this in it.) 🙂

I remember some years ago there was controversy about a cover for an ebook of Anne of Green Gables that portrayed the main character as a blonde. That’s how Aslan without a mane would seem to me. LOL.

Thanks for writing this, Icarus! I couldn’t agree more.

I loved the idea of this new Aslan. its such a refreshing way to see the story. i am here for meryl streep too!

Does it matter if Aslan is portrayed as female?

Yes; Aslan came as God to the world of Narnia as Jesus came as God to our world, and Jesus came as a MAN. We ought to strive to be faithful to the truth, as Lewis tried to be. God cannot be an impersonal “force of good” (see “Mere Christianity”) because an “impersonal force” could not forgive, and thus He must be a Person. As a Person, He must be either male or female, not both, and He is definitively male in the Bible, His written Word. Please, please be faithful to the truth, Greta. “Every good and perfect gift comes from above, coming down from the Father [note the male designation] of heavenly lights, who does not change like shifting shadows.” -James 1:17

I hope the team putting together the Netflix adaptation read this article!

Disney/Walden mentioned that Aslan’s mane was incredibly expensive to animate. Maybe, if the rumor is true, then Netflix is trying to save budget with a lioness instead.

If Netflix wants to change Aslan, though, there are probably many other things they are changing. I can still enjoy most of Prince Caspian (2008) even though I was really disappointed in how the writers changed Peter and still can’t trust myself not to cry during the night raid scene. But there is a certain point where too many changes mean it won’t feel Narnian at all and I won’t find reasons to watch.

God chose to use He/Him pronouns. Please, respect that.

Absolutely agree. Thank you, Icarus and Narniaweb!

@EJH, thanks for the reminder about the expense. Any possible explanation is kind of nice right now.

You realize the lioness story was released on April fools day, right?

Hold your internet anger till you see a second story about it from a credible source.

All of the above. Just hoping they don’t go as far as completely gender-swapping Aslan. That would be far worse than having Streep voicing him as a male character.

Are people forgetting that C S Lewis may have chosen a male lion for Aslans character, not just because lions are known the world over as ‘the King of beasts’, but also in reference to the biblical ‘Lion of Judah’? There is more significance that the depictions lions have throughout history, that many people choose to overlook, simply because they don’t agree with the intended narrative. I do agree that the role of Aslan should be voiced by a man, and not a woman, in keeping with C S Lewis’ original work.

Another problem, specifically for The Magician’s Nephew, is that having a female Aslan damages the symbolism of the creation of Narnia.

Meryl Streep voicing a male Aslan sounds more believeable considering all of these problems… which is shocking to think about.

It makes me think of a novel by Charles Williams, Lewis’s friend and fellow Inkling, “The Place of the Lion.” As with all Williams’s novels, it’s a bit hard to explain, but I’ll try anyway.

The story is about the transformation of living beings so that they are closer to their true nature / the Platonic idea of them. At the very beginning, there is a lioness that has escaped from a circus (IIRC), and she turns into a male lion. That is because the idea of a lion is masculine – a male lion is somehow more of a lion than a lioness is, partially because of the mane’s symbolism.

@EK we definitely realised that the original story was published when it was April Fools Day in parts of the world, which is why we held off publishing anything about it for more than 48 hours.

However, the highly respected Industry publication Deadline were then able to corroborate it using their own sources, and Netflix have declined to deny this story to NarniaWeb, Deadline, and every single news site that has contacted them about it.

Therefore, for now, we are left with no other option other than to treat it as legitimate news.

Great article

A roaring Aslan with a mane looks epic!

I’m very impressed that you took the time to find and quote all these passages from the books to support your points. Thank you for your service! I agree with everything you’ve said and would just like to add that Aslan is a Christ figure. One of Christ’s many biblical titles is “the Lion of the tribe of Judah” (Revelation 5:5), referring to His majesty, power, and righteous authority as King and Redeemer—tender with His children and fierce against evil.

To strip that away and make Aslan female feels deeply insulting to the figure he represents. While God is neither male nor female, His Son came to earth as a human male, and I just want His pronouns to be respected.

And in case anyone argues that Aslan is fictional and his gender doesn’t matter, there’s a scene in “The Voyage of the Dawn Treader” where Aslan comforts the children, who are sad to leave Narnia because they won’t see him again. Aslan tells them they WILL see him in their own world:

“But there I have another name. You must learn to know me by that name. This was the very reason why you were brought to Narnia—that by knowing me here for a little, you may know me better there.”

Aslan is not Jesus but he represents Jesus and changing his image changes who is being represented. I have a feeling that this adaptation I’ve been so looking forward to for years will not be the Chronicles of Narnia I was looking forward to but something else entirely. Which is a huge shame because Greta Gerwig is a genius and I couldn’t wait to see how she brought this story to life. We already have Cynthia Erivo in the role of Christ in a production of “Jesus Christ Superstar…” can we just leave Aslan alone?

I suggest voting on this production with your wallet. I just cancelled my Netflix subscription.

I am all for, in most cases, re-creating a story with different types of people playing classic roles. But in this case it doesn’t support the story and really should not happen. It’s just a silly gimmick or manifestation of political correctness that doesn’t need it to be pushed in this case. I find it hard to believe that Meryl Streep would want to do this if she understood why the change weakens the story.

Lets pettition to get this changed.

https://chng.it/vSbhZZWV7w

Let Aslan still be portrayed as a male lion with a female voice, in my opinion that would be a fine way to convey the genderless nature of the soul. Aslan transcends all of that and was never bound by the idea of duality in the way that the ‘fallen’ believe they are.

Aslan says ‘I take many forms’, many of which, I’m sure, would be gendered by others in different timespaces as ‘female’ for different qualities they associate with their idea of femininity.

I love Aslan as he is portrayed in the books, but we’ll always have the books, we can’t lose anything through exploration of these ideas through different people’s lenses. 🙂 We have to remember Aslan is just one facet of All He Is!

It’s also impossible for a lion to also be a lamb, an albatross, and a feral cat. Based on how surprisingly deep Barbie was, I trust Gerwig knows what she’s doing.

After all, he’s not a tame lion 😉

Do we even know Aslan won’t have a mane? There’s a terrific unabridged audiobook of Prince Caspian read by Lynn Redgrave, and I don’t recall her voicing Aslan being a problem.

@Jpnh, I feel like hearing a woman’s voice come out of a male-looking lion (with a mane) would be an unnecessary distraction.

Aslan is supposed to represent Jesus.Make Aslan female denies Jesus humanity.I Will NOT Support This heracy!

I don’t necessarily have an issue with Streep casting the voice. Many women have voiced male characters. If the voice works it works. Jury still out on that. I would have an issue with Aslan being changed to female and the white witch male. That just seems like a blatant slap in the face of CS Lewis. At best it would be a stab at being overly and artificially “edgy” at wost it seems like a deliberate attempt to undermine everything the author stood for. I would be so heartbroken. I got a lot of my understanding of my religon from these books’ metaphors and as such the faithfulness to the story is very important to me. I’ve been looking forward to this series, now maybe not so much.

So the rumors are true that Meryl Streep is in talks to voice Aslan. I feel like this is an odd decision. The backlash alone is reason enough for Netflix to reconsider this IMO.

But do I think a female can voice Aslan without ruining the essence of the books? Yes, I do. The writer of this article made too many assumptions.

Just because Aslan is going to be voiced by a female does not mean that Aslan will be a lioness. I fully expect Aslan to still be a Lion. Meaning, we will likely be looking at a Lion voiced by a female. Is it what I would’ve wanted? Absolutely not. I prefer a regal, but gentle voice as Aslan. But could a female voice a lion? Of course they could.

This is a great article in defense of why Aslan should be portrayed as a male lion. I appreciate the well reasoned explanation for how important his mane is. What I can’t understand is that in the same breath, a lot of people grieved about this possible casting are quick to say, “As long as Aslan is male, I’m fine with Meryl Streep voicing him.” I just don’t think that’s what is going on here. I don’t think the idea is that Aslan will look and feel like the Aslan of the books, but have a woman’s voice. For those of you saying it would help portray him as genderless, again, he’s not genderless. He’s a he. That’s the way he’s written. To alter that is not somehow in keeping with the story or intent or some deeper hidden meaning of his character. It’s a major change. You can pretend it’s not, but it is. Let’s make Narnia’s landscape/climate more like the Sahara desert while we’re at it.

I know all we can do right now is speculate, and I don’t begrudge anyone’s opinion, but that doesn’t mean it makes sense to me. Those of you who are happy with this compromise (male Aslan, female voice)…why? Why wouldn’t you want an actor with an authentically deep, regal, dramatic voice to portray the Lion?

It’s not as though any old male actor is right for Aslan, either. Danny DeVito would also be a poor choice. Meryl Streep is talented, but she can’t play any given role. She can’t successfully sound like a King, no matter how husky she makes her voice. Facts are facts. For her to even try to sound like a man won’t come across as dramatic or authentic, it will sound like Meryl Streep trying to speak like a British man. Fine if she’s recording an audiobook solo, or reading for children, but this is an ensemble cast motion picture. Which again goes back to my thought that the filmmakers aren’t really wanting her to sound like a man. And if that is the intent, it will be, as others have noted, a major distraction. It will seem farcical. I mean, when this report first came out, it looked to me like a satirical news story from The Onion or something.

Pointlessly, I suppose, I keep hoping this will all be dispelled. It’s so ridiculous that we’re in this place, scratching our heads and trying to decry it, defend it, make sense of it, or otherwise twist our brains in knots to find some sort of middle ground where it’s not as bad as it sounds but still a wacky choice. It may be as others have said, that the signs are clear this isn’t going to be what the majority of us book fans really want, and we may as well let it fail on its own. It would be awesome if there was nothing to this report, or the producers do a course correction. Time will tell. I fear this adaptation is going to get weirder and weirder the more we learn about it. I would never be happier to be wrong. But it’s starting to seem like this is quacking like a duck and walking like a duck, so it may well be a duck. All the stranger that they’re pouring such talent and money into this beloved series and then subverting it to the extreme.

Could it possibly be a “no press is bad press” kind of move? Sometimes commercials are made especially “bad” or weird just to draw attention to themselves. There was a lot of odd buzz, for example, about James Bond being played by a woman in the future, only for it to end up with reassurance that he would still be a man in future iterations (not that I am a huge Bond fan or anything; I just read things.) Well, let’s hope it’s something along those lines, anyway. Goodness gracious!

@Telmarine, as the writer of this article, i can assure you that that is not an assumption i was making.

In the opening paragraph it notes that this rumoured casting “raises the potential” for Aslan to be portrayed as female, not that it makes it a certainty.

So yes, there is still a possibility that Streep wont be cast at all, and still some possibility that even if she is cast, she will still be playing the voice as male (for example, Tails the Fox is voiced by a female in the Sonic movies).

The article is therefore not even an outright debate about gender. Its just an exploration of why Aslan’s mane, and his overall visual aesthetic, is important to the stories.

There are doubtless though many other viewpoints in this debate.

I’ve been pondering this, maybe we should consider this a a reference to Sophia. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_of_Jesus_Christ.

Also consider Sekhmet in the Egyptian tradition was portrayed with a mane. Going a bit Moses if you’re making an Egyptian reference too, but then again as a daughter of Ra, she does have a sun aspect.

Honestly, I think the silence really is a killer cause like until I see the actual Netflix social media accounts posted what they are planning in their list. I am not going to over complicate things as I hope many who are addressing the issues do so mindfully when email those involved in the project. I get the feeling the PR team just hand a random plate of news without clarity to the news reporters who later relay to the audience who reading it. I mean PR Team is not obligated to tell what going on in the progress of the productions, it more of the news reporters having asking them constantly for updates and the PR Team just could throw something out there, whether it sticks or not. Cause they been very lip-tight for months with barely any news and suddenly the water (information) flow in, it is rushed and very out there. It just not feel right especially with how Gerwig is legit surrounded those in film and so forth as there would be discussion of “is this right” questions be appearing before pre-production. I smell a stunt, a very messy stunt I do say so myself. Either way we need to look out for events that Netflix will reveal more stuff cause my suspicion is at Tudum, Netflix’s Version of comic-con.

Anyway, hope to get more of this.

There’s a saying I heard once, when passing through Beruna in Narnia: “By the Lion’s mane!” I actually heard it a few more times in Lantern Waste the next week. It was said with such a hearty conviction of things that are true and just.