Why Uncle Andrew Didn’t Just Become a Scientist | Talking Beasts

Podcast: Play in new window | Embed

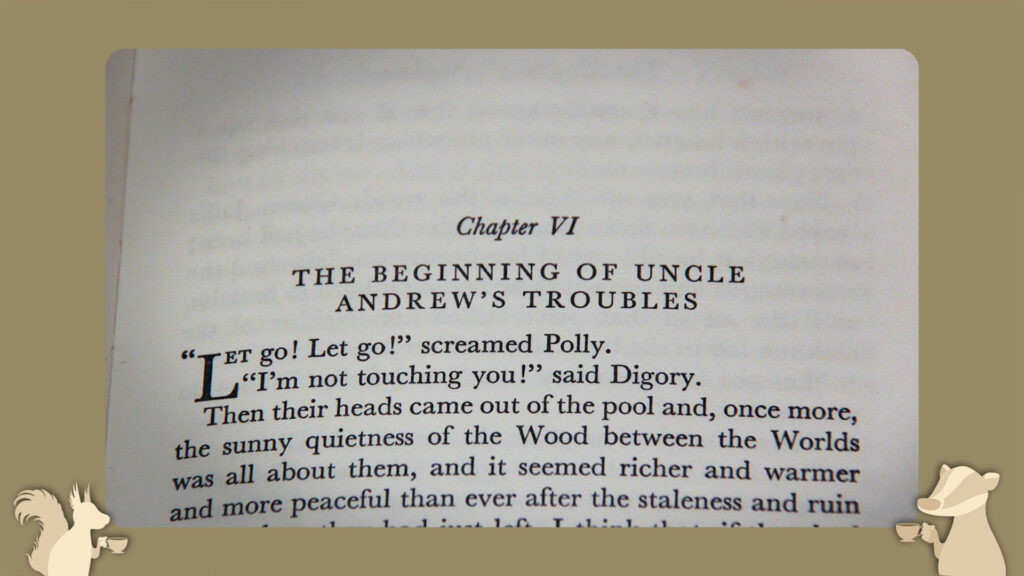

In this episode, the podcasters discuss The Beginning of Uncle Andrew’s Troubles in The Magician’s Nephew, including more similarities between Andrew Ketterley and Queen Jadis.

View this episode’s post-show chatter.

Listen to more episodes of Talking Beasts: The Narnia Podcast.

That’s interesting that for Gymfan the London scenes in the middle are the parts of the book she’s tempted to skip. When I was a kid, I only liked fantasy books, but I always enjoyed this part of the story.

I never really got the impression that the Wood Between the Worlds was particularly good or holy. I see it as sort of neutral. After all, Jadis didn’t have a similar fainting fit when she was in the unspoiled Narnia or in Aslan’s presence. I always thought along similar lines as Glumpuddle about her reaction to the WBTW. She’s the kind of person who always wants something to conquer and there’s nothing to conquer in the Wood nor any way there will ever be anything to conquer.

I don’t think I’ve ever been disturbed by Polly’s treatment of Jadis in this chapter. I mean she did deliberately destroy a whole world out of pride. If anyone deserves to be left in the Wood Between the Worlds, she does.

I think there are actresses who could pull off looking ten times more alive than everybody else, but it’s hard to do the beauty thing. Whenever there are characters in a movie or on a show who are supposed to be really beautiful or really ugly, I feel like the viewer is usually going to be going, “they’re not pretty” or “they’re not that bad.”

Similar to what Gymfan said, I never thought of the “mark” as being like a physical mark. I thought it was more like a facial expression. Doesn’t the book describe both Uncle Andrew and Jadis as having a greedy look on their faces at one point?

I’d like to thank Gymfan and Glumpuddle for pointing out all these little nuances I never thought about before, like how even though Jadis comes across as funny at this point in the book, she’s not just strong, she’s intelligent, or how, that being said, while Uncle Andrew is generally less competent than Jadis, when it came to considering the dangerous possibilities of other worlds, he was smarter than she. (Of course, you could argue Jadis is so powerful that she doesn’t need to plan ahead.)

I think the answer to the question in this episode’s title is there were plenty of famous scientists in London at that point in history and there weren’t many famous magicians, so that appealed to Uncle Andrew.

By a coincidence, I’ve been participating in a Bible study about the book of Exodus which talks about the holy of holies.

I kind of wish this episode had been longer. I understand thought that this part of the book isn’t the podcasters’ favorite (and from Glumpuddle’s comment about Jumping the Shark, it sounds like the next part is even less of a favorite.) I get that it doesn’t really lend itself to the kind of philosophical discussion they did in previous Magician’s Nephew episodes, being more about humor and suspense. (Kind of like what they were saying in the beginning about Top Gun: Maverick.) I do wish they’d talked more about Uncle Andrew being silly “in a very grownup way.” Glumpuddle described him as comic relief at this point and there’s truth to that, but I find it psychologically interesting how he goes back and forth between thinking he can charm Jadis and being terrified of her.

P.S.

Could the quote Rilian was trying to remember have come from Peter Pan? “Children are gay and innocent and heartless.”

“The serious magical endeavour and the serious scientific endeavour are twins: one was sickly and died, the other strong and throve. But they were twins. They were born of the same impulse. I allow that some (certainly not all) of the early scientists were actuated by a pure love of knowledge. But if we consider the temper of that age as a whole we can discern the impulse of which I speak.” – C.S. Lewis, The Abolition of Man

Uncle Andrew responded to Jadis in the same way that humans tend to respond to evil’s presence, in whatever shape or form. When we are facing something that is evil, we are terrified by it because we can see how awful it is. But when we are not facing it, we can convince ourselves that it isn’t as awful as we remember.

Col Klink, you mentioned the book of Exodus. The Israelites are a perfect example of this idea in action. When they were enslaved and tortured by the Egyptians, they cried for release (Exodus 3:7). God sent Moses to free them from their oppressors, but once they were freed, they forgot how cruel their slavery had been. They talked about how much better life in Egypt had been, and how they wanted to return (Numbers 14:4).

When we are not being faced with the reality of evil, we have a strange tendency to romanticize it.

I think Eva Green would play a good Jadis.