Why C.S. Lewis Said Narnia is “Not Allegory at All”

Look for “Did you know” articles on NarniaWeb on the first of every month.

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary an allegory is defined as:

1: the expression by means of symbolic fictional figures and actions of truths or generalizations about human existence

also : an instance (as in a story or painting) of such expression

2: a symbolic representation

So, using this definition, are The Chronicles of Narnia an allegory?

Most say yes.

The Narnia series is certainly full of symbolism. It is pretty much impossible to ignore the very pointed use of capitalizing Aslan as “He” at the end of the series. It is easy to see parallels between a deity dying on a Stone Table in a traitor’s stead to appease Deep Magic and a deity dying on a cross in the place of sinners to appease a higher power’s justice.

C.S. Lewis himself seems to have supported these symbolic readings.

In a letter to a mother whose son, Laurence, was worried that he loved Aslan more than Jesus, Lewis responded this way:

But Laurence can’t really love Aslan more than Jesus, even if he feels that’s what he is doing. For the things he loves Aslan for doing or saying are simply the things Jesus really did and said. So that when Laurence thinks he is loving Aslan, he is really loving Jesus: and perhaps loving Him more than he ever did before. Of course there is one thing Aslan has that Jesus has not–I mean, the body of a lion. (But remember, if there are other worlds and they need to be saved and Christ were to save them as He would–He may really have taken all sorts of bodies in them which we don’t know about.)

Letters to Children ~ Lyle W. Dorsett and Marjorie Lamp Mead

This interpretation of Aslan by Lewis is strikingly similar to the conversation Emeth has with Aslan in The Last Battle (which had not yet been published at the time he wrote to Laurence’s mother).

But I said also (for the truth constrained me), Yet I have been seeking Tash all my days. Beloved, said the Glorious One, unless thy desire had been for me thou wouldst not have sought so long and so truly. For all find what they truly seek.

The Last Battle ~ C.S. Lewis

However, Lewis did not support an allegorical reading of Narnia.

In order for a book to be classified as an allegory it has to have more than just symbols.

The site litcharts has an extensive page on what makes an allegory an allegory, but here is the relevant part when it comes to interpreting Narnia:

Although all allegories use symbolism heavily, not all writing that uses symbolism qualifies as allegory. Allegories are characterized by a use of symbolism that permeates the entire story, to the extent that essentially all major characters and their actions can be understood as having symbolic significance.

While Aslan certainly seems like a symbolic character, other characters in the story do not have counterparts in the same way. The White Witch does not represent Satan. The four Pevensies do not represent some grouping of virtues. Puddleglum is inspired by a real-life person, but does not actually represent gardener Fred Paxford.

By an allegory I mean a composition (whether pictorial or literary) in which immaterial realities are represented by feigned physical objects, e.g. a pictured Cupid allegorically represents erotic love (which in reality is an experience, not an object occupying a given area of space) or, in Bunyan, a giant represents Despair.

Letters of C.S. Lewis ~ W.H. Lewis and Walter Hooper

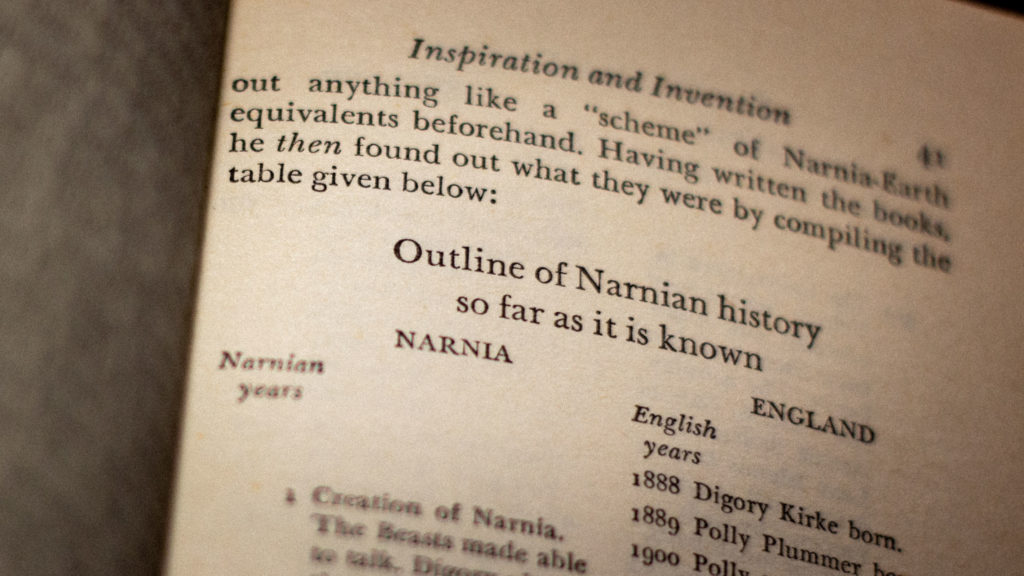

Basically, in order for a written work to be allegorical, everything must represent something else. Compare Narnia with Lewis’ The Pilgrim’s Regress. Every character in that book represents someone or some idea in the real world. Of course, not every allegory is quite as overt as Regress (it’s easy to understand what each character represents when they have names like “Mr. Enlightenment”), but allegories are symbolic all the time. Narnia is not.

If Aslan represented the immaterial Deity in the same way in which Giant Despair represents Despair, he would be an allegorical figure. In reality however he is an invention giving an imaginary answer to the question, ‘What might Christ become like, if there really were a world like Narnia and He chose to be incarnate and die and rise again in that world as He actually has done in ours?’ This is not allegory at all.

Letters of C.S. Lewis

So, if Narnia is not an allegory, what is it?

Lewis referred to Narnia as a “supposal”.

Returning to Merriam-Webster, a supposal is defined as:

1: the act or process of supposing

2: something supposed : HYPOTHESIS, SUPPOSITION

Lewis wrote about this concept multiple times.

All your points are in a sense right. But I’m not exactly “representing” the real (Christian) story in symbols. I’m more saying “Suppose there were a world like Narnia and it needed rescuing and the Son of God (or the ‘Great Emperor oversea’) went to redeem it, as He came to redeem ours, what might it, in that world, all have been like?” Perhaps it comes to much the same thing as you thought, but not quite.

Letters to Children

Unlike allegories, supposal as a literary term does not seem to exist outside of Lewis’ own writings. But, for context, there is a famous fictional work that uses similar phrasing:

“Suppose there was a bright fire in the grate, with lots of little dancing flames,” she murmured. “Suppose there was a comfortable chair before it–and suppose there was a small table near, with a little hot–hot supper on it. And suppose . . . “

A Little Princess ~ Frances Hodgson Burnett

Indeed, the “supposing” that Sara Crewe engages in throughout A Little Princess might help readers understand the concept as Lewis presented it. Sara imagines throughout the book by using the word “suppose”. Only instead of supposing as Sara does that a single bite of a bun is a whole dinner, Lewis supposed that Jesus would appear different on another world, and yet do the same things. And, although it happens within the story instead of being the basis of the story, the significant times that Sara supposes come true in some fashion.

Lewis also considered his Space Trilogy to be supposals rather than allegorical.

So in Perelandra. This also works out a supposition. (‘Suppose, even now, in some other planet there were a first couple undergoing the same that Adam and Eve underwent here, but successfully’).

Letters of C.S. Lewis

The line between allegory and supposal can seem a bit blurry the way Lewis describes it, but the distinction is still there.

Allegory and such supposals differ because they mix the real and the unreal in different ways. Bunyan’s picture of Giant Despair does not start from supposal at all. It is not a supposition but a fact that despair can capture and imprison a human soul. What is unreal (fictional) is the giant, the castle, and the dungeon. The Incarnation of Christ in another world is mere supposal; but granted the suppposition, He would really have been a physical object in that world as He was in Palestine and His death on the Stone Table would have been a physical event no less than his death on Calvary.

Letters of C.S. Lewis

Essentially, “supposing” is simply the basis of a story that asks “what if?”. What if the main characters of Hamlet were lions? What if Abraham Lincoln hunted vampires? What if all humans decided to work together to create a better future and then built spaceships to study new life and new civilizations?

Did Lewis intend The Chronicles of Narnia to be heavily symbolic?

Yes, and also no.

As with any piece of writing, Narnia transformed over time. Lewis wrote about the process more than once, but perhaps the best reference for this is from the essay Sometimes fairy stories may say best what’s to be said.

Some people seem to think that I began by asking myself how I could say something about Christianity to children; then fixed on the fairy tale as an instrument; then collected information about child-psychology and decided what age-group I’d write for; then drew up a list of basic Christian truths and hammered out ‘allegories’ to embody them. This is all pure moonshine. I couldn’t write in that way at all. Everything began with images; a faun carrying an umbrella, a queen on a sledge, a magnificent lion. At first there wasn’t even anything Christian about them; that element pushed itself in of its own accord.

. . .

I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.

Narnia is not an allegory because it does not fit the definition of an allegory. However, Narnia does ask “what if?” and then uses symbols to answer that question.

I haven’t had time to read this article in full just yet, but it looks really interesting and very helpful, thank you! (I wince every time I see a reviewer, usually disparagingly, referring to Narnia as “allegory” when, in fact, it’s not.) Just wanted to point out one issue near the start, with the sentence: “It is pretty much impossible to ignore the very pointed use of always capitalizing Aslan as “He”.”

As far as I’m aware from reading the Chronicles (unless there’s a difference between the UK and US editions?), the capitalised “He” for Aslan is almost never used at all. I’m almost certain it only happens once in the entire series, in the very last paragraph of The Last Battle: “And as He spoke, He no longer looked to them like a lion…” I’ve always thought that passage stands out precisely because we’ve never had capitalised pronouns for Aslan before in the Chronicles, until this final scene. Perhaps the NarniaWeb team could check this and fix that line in the article?

Many thanks and I’m really looking forward to reading this and future “Did you know?” features. NarniaWeb is the best Narnia website and online community I’ve ever found and I absolutely love it!!

Whilst I’m definitely not an expert on theories of literature – one movie which I think is a really good example of pure allegory, for anyone who is interested in exploring the concept, is the original movie adaptation of Snowpiercer (not the more recent TV series). Whilst it perhaps doesn’t quite fit all of your definitions outlined above, I would consider it to be pure allegory in the sesne that it’s a movie which can only really be viewed in a metaphorical context, and not at all in a literal context – in this case it’s a story about a train, where the train is an metaphor for social inequality within society.

Viewers who don’t pick up on the allegorical nature of the story are often left confused by the movie, and most of their most frequently raised questions tend to be about the physical mechanics of the situation in a literal real world context – the answer to all of those questions though is inevitably – “That’s the point of the story, it’s an allegory for class struggle, you aren’t supposed to view any of it literally”

In that sense then it’s very easy to see why Narnia is not an allegory, in that the stories can be interpreted as literal (albeit fantasy) stories, and that not everything in the stories is a metaphor that contributes towards some grander theme (as I feel is the case in Snowpiercer)

Thank you, Daughter of the King, for writing this excellent article!

It clarified what has long been a bit of a confusing subject for me.

Well done! I especially appreciate how you built to this defining quote from C.S. Lewis himself: “I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralysed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or about the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.”

You are correct. That typo wasn’t caught in editing. Thanks for pointing it out!

Thank you very much, Daughter of the King!

I have often been frustrated online by people using the word for a much wider meaning, when they needed to talk of ‘imagery’ or ‘representation’ or even really meant ‘analogy’.

Am I the only person in the world to have formally studied an allegory (The Pilgrim’s Progress) in Second Year English Literature at University before I was introduced to the Narnia books?

You’re welcome! I’ve now had time to read the rest of the article and it’s an excellent concise essay that explains the point really clearly. Thank you again!

You know not only do people seem to expect every aspect of Narnia to represent something (ala Pilgrim’s Progress or Animal Farm) but they seem to expect the characters, like Lucy, Peter and Shasta, to correspond to a biblical figure. The only real examples I think of this besides the obvious one of Aslan are King Frank and Queen Helen, the equivalents of Adam and Eve, and even then their lives don’t perfectly match up. (We never hear about one of their sons killing his brother, for example.)

I’m not really sure where the idea came from that if a fantasy adventure book has a biblical message, as the Narnia books do, its plot must be a retelling of one of the historical books of the Bible with names and details changed. Maybe it’s because most people originally read the Narnia books as kids and kids remember narratives better than themes. Or maybe it’s because modern Christian authors have written books like that, such as the Passages series by Paul McCusker or the Kingdom series by Chuck Black, and so that’s what modern Christian readers automatically expect. (I liked the Passage series, BTW, and I don’t remember disliking the Kingdom series; I’m not trying to bash anyone with this comment.) I think a neutral reading will show that the Narnia books are original stories with original characters that have biblical themes. (The only parts of them that count as versions of biblical events are the creation of the world, the death and resurrection of Christ and arguably the final judgement. And even those are far from exact in the details.)

P.S.

As well written as this article was, I’m compelled to argue that The Lion King is not a retelling of Hamlet. The creators may have said that out of pretension but there aren’t any real thematic or structural similarities between the two, just a few similar plot points. (You might as well say Prince Caspian was Hamlet with Narnians.) West Side Story, which has many structural and thematic parallels to another famous Shakespeare play, would be a better example.

I’m admittedly quite guilty of “allegory – hunting” myself; I believe this is the case with many Narnia readers simply because the books do contain a few parallels and symbolism, which encourages the curious nerds among us to look for more, or even to assume that there simply must be more. I’ve come up with a half dozen theories as to what each Narnia book represents, but it began with the obvious hints at the gospel in LWW.

What annoys me more is not when people simply mistake Narnia as allegory, but when they criticize it for being one. Tolkien, with his strong dislike for allegory, seems to have started this criticism with his own dismissal of the Narnia books on the grounds that they were too openly symbolic.(Though in some other cases people have a problem with the books’ symbolism simply because they hate Christianity or religion in general, and so accuse Lewis of “having an agenda”- while at the same time giving books with a clear atheist agenda a pass.)

I remember that my professor in college said that stories such as the Narnia books are independent creations on their own. So you have references in them rather than allegories. This is true even of references to the Bible, which is different than parallels. I think that works well with the supposition idea. Narnia is its own world and not an allegory for another place.

To be fair, Disney doesn’t have the best track record for accurate adaptations. The source material for stuff like Mulan and Sleeping Beauty is pretty different from the end result, so maybe it’s dissimilarities don’t stick out as much if The Lion King get’s lined up with the other adaptations.

Admittedly I have not read the original version of Hamlet, but I imagine Shakespeare couldn’t be more offended by the Lion King than say, Rick Riorden was with Disney’s awful Percy Jackson adaptations.

Hey, I just realized something extremely cool: Puddleglum does the exact same thing in “The Silver Chair”! After putting out the witch’s fire, he does this awesome little monologue where he says something like “SUPPOSE your black pit of a kingdom is the only real world. In that case, the made-up things are a good deal more important than the real ones!” He wasn’t giving in to her magic, he was basically saying, IF she’s right, THEN he’s still going to stand by what he believes. He’s on Aslan’s side, even IF there isn’t any Aslan to lead it. He’s going to live as like a Narnian as he can, even IF there isn’t any Narnia! He knows there is an Aslan and a Narnia, but he’s playing with the what-ifs. That’s the fun of writing fiction IMO. 🙂

PS: To my fellow coders:

if (Narnia == allegory) {

ImAMonkeysUncle(true); // 🙂

}

Thank you for this description.

they love this.