NarniaWeb Set Report #3: Roger Ford & Richard Taylor

INTERVIEW: Production Designer Roger Ford

INTERVIEW: Production Designer Roger Ford

Transcription by Coraline

We interviewed Roger Ford (IMDB) at the enormous 360-degree castle courtyard set. In addition to the first Narnia film, Ford also designed sets for Peter Pan (2003) and both Babe films. This will be his last Narnia film, and he is definitely going out with a bang: (Thanks to Coraline for the transcription)

Ernie Malik: Folks, you can introduce yourselves. This is Roger Ford, Production Designer… extraordinaire, I might add to that, for both the first film and the second film. And equally impressive as far as the sets he had to imagine, based on the fact that he didn’t have much to work with, did you Roger? Is that a good enough buildup for you, Roger?

Ford: Keep going, keep going… (laughter). Welcome, welcome.

Q: So, we hear this is your favorite set?

Ford: Well, this is certainly my biggest set. We built some big stuff for the second “Babe” film, but I actually think this is bigger.

Q: Can you talk a little about the influences?

Ford: We started off looking at a castle in France, called Pierrefonds Castle, as a location. And that gave us a feeling of size that we wanted. We were thinking, you see, that the Telmarines who are now predominant in Narnia, having chased the Narnians back into the forests and slaughtered most of them, came from pirates, long ago. A thousand years ago. They were pirates that were shipwrecked on an island and found themselves in a cave where there was a portal into Narnia. So that’s the beginning of Telmar and the Telmarines. Telmar was always there in the first film, but just next to Narnia. So we started to think about pirates, and we started to think about Peter and the children being English, and wanting Prince Caspian to somehow be different. We didn’t want another bunch of English people, in other words. It wasn’t going to be interesting. And I said to Andrew, “Why don’t we make them French?” Because there’s always been stuff between the English and the French. It kind of sets up a nice situation. And he said, “Well, let’s go further. Let’s imagine perhaps that they’re Spanish from the Iberian Peninsula. Which kind of fits better with pirates as well. So this castle here, the influences for it are Spanish, a Spanish castle. We did a lot of research and it’s pretty close in many respects. Even that detail up on the balcony [points up], the diamonds came from locations within Spain, references. We wanted it to be rather oppressive. So the color is not a happy, cheerful color. We wanted it to feel immense. These are not very nice people, Telmarines. Particularly Miraz. So we started to think about Fascists and the imagery, you know, war. So we started to develop the eagle and it almost has a 1930s influence. But they’ve definitely got a Fascist feeling. And then, as another symbol for the Telmarines, we thought “pirates”, and what would be a good symbol that we can use on banners and flags, and we developed the idea of the compass. And we’ve used that symbol in the heraldry and in the Great Hall in the floor. It’s almost, if you can imagine, Italian Fascists sort of using something like those. And these stories are all about the last War, basically, they were written after the War ended. And the Lion and England and good versus evil.

Q: How do you get your head around something this large? What’s the first thing you start on? Do you have a vision of this and you work toward it?

Ford: We knew what size we wanted, because Andrew had seen this castle in France, and we use what’s called pre-visualization in the film, which is a visualization of the film in a computer before the set gets built, even. So pre-viz had taken the plans of that castle quite early on, this is Pierrefonds, and put them into the computer and started to work out the action in the courtyard. So that, as we started to design this thing, we used the same sizes as had been used in that castle. We were, of course, able then, while building the set, to give Andrew much more of what he wanted for the action. So all these stairs [points around] are specifically designed for the action of what we call the Raid in the film, when the Narnians try and take the castle. And they get surrounded by archers, all crossbowmen, and quite unpleasant things happen. So it’s purpose-built for the film. And everything here, the way it’s all planned out, is built to suit the film, rather than just “here’s a set, do what you want to do with it.”

Q: Did you feel a sense of intimidation about the scale?

Ford: You know, basically, it’s just more carpenters. It’s no different… I mean the scale, it’s no different to designing any other set, except that it’s more people, more money.

Q: You carry these themes into the Great Hall set as well?

Ford: Yes. This is actually the exterior of the Great Hall. It kind of loosely resembles it, so this big window here, you’d have in the Great Hall, that is vaguely that shape. We had some very big iron chandeliers hanging in the Great Hall, hanging from eagles like this, but made of like cast iron and bronze and these huge chandelier things all around the Hall. It’s quite impressive, actually.

Q: Is the coronation going to be inside the Great Hall, or will it be outside in the courtyard?

Ford: The coronation is in the Great Hall. It has already been shot.

Q: That’s Miraz’ coronation?

Ford: Yes.

Q: And Caspian’s?

Ford: Caspian’s [coronation] is in [the courtyard].

Q: Obviously there’s so much detail, there’s only so much to be picked up in the movie in the filming. Have you been around with a camera, looking 360, capture for the DVD or something, because obviously it’s coming out eventually…

Ernie Malik: We have, Roger, yes. (group laughter) This, Aslan’s How, and the Great Hall so far are the 3 sets we’ve done the 360 [degree] stuff on.

Q: You don’t have any of the same sets from the first film, so how much of that did you carry over in terms of themes or of the look of the film?

Ford: Well, there is the same set, but we don’t know it is when we first see it. They come into Narnia, the children. In this film they come from an underground station in London. In the book, it’s a country railway station. The underground station seemed to be visually more interesting, and we’d been on the station in the first film. And then of course, you have this wonderful tunnel effect in London underground stations. And we went to New Zealand to find where the children would emerge in Narnia, and we found this beautiful beach called Cathedral Cove, which has a tunnel through a rock. It goes from one beach to another beach through a tunnel. So there’s this great transition where they’re in the underground tunnel, and gradually they go through into this rock tunnel on the beach in New Zealand. Then, they look up and they see ruins up on the headland, and make their way up there and eventually discover that it is, in fact, Cair Paravel, the castle of the Narnians in the first film. So we had to recreate, exactly, the Great Hall of Cair Paravel, in plan on a location on the headland as a ruin. But it’s a subtle ruin. The kids can’t quite figure it out until they stand where the thrones used to be, and they’re looking down and they start to see the columns. So that carried on through from the last movie. But after that, this is a much darker film, and it’s more Shakespearean in many ways. I mean, the uncle kills the father (laughter) and has a son and he wants to kill Prince Caspian. It could be Shakespeare.

Ford: Well, there is the same set, but we don’t know it is when we first see it. They come into Narnia, the children. In this film they come from an underground station in London. In the book, it’s a country railway station. The underground station seemed to be visually more interesting, and we’d been on the station in the first film. And then of course, you have this wonderful tunnel effect in London underground stations. And we went to New Zealand to find where the children would emerge in Narnia, and we found this beautiful beach called Cathedral Cove, which has a tunnel through a rock. It goes from one beach to another beach through a tunnel. So there’s this great transition where they’re in the underground tunnel, and gradually they go through into this rock tunnel on the beach in New Zealand. Then, they look up and they see ruins up on the headland, and make their way up there and eventually discover that it is, in fact, Cair Paravel, the castle of the Narnians in the first film. So we had to recreate, exactly, the Great Hall of Cair Paravel, in plan on a location on the headland as a ruin. But it’s a subtle ruin. The kids can’t quite figure it out until they stand where the thrones used to be, and they’re looking down and they start to see the columns. So that carried on through from the last movie. But after that, this is a much darker film, and it’s more Shakespearean in many ways. I mean, the uncle kills the father (laughter) and has a son and he wants to kill Prince Caspian. It could be Shakespeare.

Q: The decision to move it here, was it because of the forest? Or just in general, in your opinion?

Ford: I think we looked at the studios in Berlin, and we considered Australia, you have to go through all the possibilities.

Q: I mean, why not stay in New Zealand? There’s a lot of wide open space there.

Ford: The problem was the delivery date for the film, and therefore, the time we had to make the film and have it finished. And it put us across Winter and Summer in New Zealand… no, the other way around. Summer and Winter in New Zealand are Winter and Summer here. We don’t want Winter. Well, we started off in Summer in New Zealand, and then as winter came on, we had to move here and wait for the Spring to come on. So those are the sort of things that make the decisions . I think we came to Prague because, well, I’m certain financial considerations played a big part, but also it’s in the middle of Europe, and a lot of our locations are in Holland, Slovenia, you know, also in the Czech Republic.

Q: Although it’s a sequel, the world has changed so much. It’s still Narnia, but it’s not really Narnia, because so much time has passed. How did you approach that, coming into this design-wise?

Ford: Years have passed. And Narnia has been overrun by an invading army who were pretty brutal, so the Narnians have retreated to the woods, and as far as the Telmarines think, they’ve almost been eliminated. But they haven’t, they’re still in there. So we’ve got this contrast between a rather somber architecture of the Telmarines, and the fact that they’ve cleared the forest as far as they can. All around the town and the castle, they’ve cleared the forest. And it’s all rather depressing. Contrasted with when you go into the forest, it’s very beautiful. And when Lucy finds Aslan, we prettied up the forests of New Zealand with our greens department, and it looks absolutely fantastic. All the forest stuff is really beautiful. There’s actually a set, I don’t know whether you’ve seen it, you should probably poke your head in there.

Ernie Malik: Stage 8. I just took them over there.

Ford: It’s just starting to take shape now. We imagined that the six or seven oak trees are the custodians of Dancing Lawn, sort of the guardians. And that’s where the Narnians gather. So we’re building that set at the moment.

Q: What was the decision about building [the courtyard] outdoors? Besides it being outdoors, was there a decision as far as building a sound stage and doing sections or doing things like that, which normally would be done, did you?

Ford: Well, yes, and of course, it’s a mostly night scene, where you have to shoot all night, which is very inconvenient and unpleasant. But this wouldn’t fit in any stage in this country or any other.

Q: But Instead of doing one big huge place, you could’ve just built certain sections. Like, if you know that you have certain scenes in certain sections. Why didn’t you do…

Ford: You could have done that, yeah. But there’s something to be said for sort’ve just being able to do that [indicates camera pan with his hands]. You can often pick when you’ve cheated. But with this, we don’t have to. And I should point out that what you see here will be at least two or three times higher in the movie. All around here [points up] will be extended three times as high. And, we worked on the exterior a lot to get it looking really oppressive and huge. George Miller on the first Babe film taught me something. We were trying to build the farmhouse for Farmer Hogit and he said, “You know Roger, did you watch Psycho?” And I said, “yeah sure, who didn’t?” He said, “Do you remember the motel?” I said “Yeah, clearly.” He said, “That is a character in that film. One of the characters is the building. That’s what I want the farmhouse to be.” So, in a sense, when we tried to develop the exterior of the castle, I’m trying to put a character into the movie and make it reflect the Telmarine culture. It’s imposing in its own right.

Q: Do we actually see the exterior [of the castle] from the village?

Ford: You’ll see, quite often, the exterior. It’s being built in miniature in New Zealand by Weta. And the town is built in miniature. And the castle…well, actually there’s already a poster of it on the net, the first version of it. It has changed slightly since then. [NOTE: Ford is referring to the concept art that leaked onto the Internet back in January. A more recent version was included with the first set report] But it’s built on rock pinnacles. We found a location in Germany called Bastak which has enormous rock pinnacles where there was once a castle.

Q: Can you tell us if you’re going to be involved in future Narnia films?

Ford: No, I won’t be. I have had four great years with Andrew Adamson. The next movie has already started. So, apart from the fact that four years of Narnia seems like enough, it’s been brilliant and I think it’s great to hand it over to a new team, a new director, new designer.

Q: How has production design changed since you first started?

Ford: It’s basically computers, isn’t it? You know, the last Star Wars had so much blue screen and green screen. And you think, “Hang on, am I going to have a job in five or ten years time?” (laughter). But, what actually happened is exactly the opposite. My job has become incredibly much more interesting and exciting because all these possibilities open up now. You can go to locations now that you couldn’t have used because you’d see electric lines or clouds going across the landscape and say “well, we can’t use it.” Now you can use it because you know you can get rid of those things and add things to it. So it has actually made my work much more interesting, exciting, and challenging. It’s brilliant.

Q: A lot of times when you design something, you have to have a painter paint it, and if you want to make a change to that, you can actually change it with the computers…

Ford: Absolutely, it’s brilliant. You can go inside your set before it’s built. We started doing that on the second Babe film, and that was the first time I did it. We built this hotel which was like a four story foyer with staircases going all the way up it. There were a lot of scenes in there and Director George Miller wanted to see how it was going to work. So it was all put into a computer and we were able to walk up the steps before we even put a nail into a piece of wood. So it’s fantastic to be able to do that. For instance, now if you go out to Ústí where we’re filming Aslan’s How…We can take photographs of the set and put in what is going to be added and show Andrew and he can guide it and make comments about it way before that part of the movie is finished.

Q: Can you talk a little about Aslan’s How?

Ford: We always go back to the book and look at the illustrations by Pauline Baynes. And then we think “Well, we have a movie to make here, so what can we do to go a few steps further?” So that when the children who’ve read the book and seen the illustrations go see this movie, they’ll be re-inspired. So that it’s even better than they thought possible. The single combat between Peter and Miraz happens almost like in a boxing ring. Looking at that, you think, “Well, that’s not going to work, who’s going to be impressed by that?” So, we developed Aslan’s How to have a kind of ruined temple out in front of it. Which then gives us a stage to work off, something interesting for them to jump on, bits of rock and ruin. It kind of sets it into the landscape rather than just two guys fighting. So that’s one thing we did. And then, Andrew developed the battle wanting it have something other than just the two armies facing each other on the landscape.

Q: How is it combining all this in the computer?

Ford: Well, this is where the pre-viz comes in really useful. We can do schemes and schematics of frames in the movie now and you can say, “This foreground part is one pass, and this bit we’ll build in miniature, and the background from New Zealand…” So you know the way the film will be made up before you do it. So I know what I am providing, and I know what the supplementary stuff will look like. It’s all to do with very careful planning.

Ernie Malik: I’m going to throw the last one out and then we’ll let Roger get back to work. Roger, they were curious about the hieroglyphics in Stage 6 that go around the Table and what you’ve got as your ceiling around the How. Now you can be cheeky Roger or you can… (laughter)

Ford: I was asked this question on the first movie, and I’m going to say the same thing: If you want to know what it means, you gotta ask Aslan.

(laughter)

INTERVIEW: Richard Taylor (Head of Weta Workshop)

INTERVIEW: Richard Taylor (Head of Weta Workshop)

Transcription by Steve from IGN

We interviewed Richard Taylor (IMDb) in the lunch tent. Richard received five Academy Awards for his work on The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Weta Workshop also worked on King Kong and 30 Days of Night. I think all of us had a blast interviewing Richard. When we asked him questions, his eyes would light up and he’d smile from ear to ear. He is so visibly passionate about his job and he loves to talk about what he does.

Q: You’ve been involved in this movie doing miniatures?

Taylor: We’re doing some costuming work, weapons, armor, and miniatures. There are going to be massive miniatures. We coined that phrase “big-atures” on The Lord of the Rings and this is going to outdo them all. The miniature we’re doing for Miraz’s castle is 24th scale, village, and exterior location at 100th scale and both miniatures are bigger than this tent. They are colossal things.

Q: How has it been working with Roger Ford?

Taylor: Just very good correspondence through Roger’s art directors. We have a production team that daily coordinates with us. They’ve 3D-modeled it. It’s amazing how the world has changed in the last five years for us all. He’s 3D digitally modeled the castle, we get that data, we put that through our 3D milling machines and our 3D printers, we print pieces and mill pieces. We’ve had to custom-build some machines to actually manufacture the coarse lines in the miniature and so on. It’s been quite a mission. It’s the same with the swords as well. We had two and a half months to deliver two and a half thousand weapons, so unlike the previous film we couldn’t hand-grind the weapons. We actually purchased a very large 3D milling machine and digitally milled all the blades out, running 24 hours a day, seven days a week to actually get all of the saw blades made in time and then cast urethane hilts onto them all.

Q: Why is it so important to get such a level of detail on the costumes and weapons?

Taylor: I guess that’s a good debate. People often come to the workshop and ask us why we are being so fanatical, but the real world is a cluttered world. It’s cluttered with history and detail and a culture. Just walking around this city, Prague, it’s saturated with details and it shows a lineage and history which dates back hundreds if not thousands of years. That’s my feeling with proppage, weapons, and armor. If it doesn’t have that depth of detail, you can’t help to suggest that the world exists outside of the picture frame. If it’s a shallow visual image, it suggests that you are watching a film, but if it has a level of saturation and detail it suggests that there’s a history there that spans around the world that sort of can bookend it, that exists beyond the movie.

Taylor: I guess that’s a good debate. People often come to the workshop and ask us why we are being so fanatical, but the real world is a cluttered world. It’s cluttered with history and detail and a culture. Just walking around this city, Prague, it’s saturated with details and it shows a lineage and history which dates back hundreds if not thousands of years. That’s my feeling with proppage, weapons, and armor. If it doesn’t have that depth of detail, you can’t help to suggest that the world exists outside of the picture frame. If it’s a shallow visual image, it suggests that you are watching a film, but if it has a level of saturation and detail it suggests that there’s a history there that spans around the world that sort of can bookend it, that exists beyond the movie.

Q: At this point in your experience, with The Lord of the Rings movies and the first Narnia movie, is this an even bigger scope?

Taylor: This is an interesting one. The miniatures, although there are not a huge number of them, are the biggest and most challenging miniatures we’ve built to date and we’ve built some pretty challenging miniatures. On King Kong, we built 54 miniatures over that year, but these miniatures are very challenging on a technical level. We’ve pushed ourselves further than we ever have before with our weaponry. For Miraz’s weapons, we actually used 3D modeling technology, then printed them in wax, and used lost-wax casting processes to actually manufacture the ornateness of the weapon. Because we just didn’t have the skills to do that incredibly delicate filigree in any other way. It’s been really wonderful to challenge ourselves to meet Andrew’s expectations. We knew going into the movie that he’d want to step it up to a whole other level and it’s been really exciting being asked to do that. Miraz’s armor, they cast the actor very late in the piece so we’ve been holding off, waiting to find out who the actor would be. Once the button got pushed and we could start making it, we’ve been able to turn around this very elaborate armor and get it on set it time. It’s been wonderfully challenging, but a great experience.

Q: Is there anything that made you sweat on this movie?

Taylor: Yes, there have been a number of things actually, time being the great challenge. We understand that you can never push back on time, you understand that the whole thing is a complex process of interlaying of actors and writing and design. The thing has to build a momentum before it comes to a conclusion that you can start building from and we want to be respectful of that, even though we’ve been putting our hands up squealing a little bit saying ‘Let us get going.’ (Laughs) There is nothing you can do about it; you just make sure that the crew are ready to go when the button gets pushed. We would like to think that we’ve become capable of turning on a dime to get a lot a stuff done very quickly, so we’ve managed to produce a lot in a very short time for this one. That’s been incredibly exciting in the workshop, there’s nothing like that momentum and that feeling of productivity. You know we were shipping half a ton of product every two weeks out the door.

Q: Are you more involved with this movie than with the first movie?

Q: Are you more involved with this movie than with the first movie?

Taylor: We’re about the same amount. On the first one, we played a much bigger part in the creature design, but because Howard [Berger] did the creature suits for this one, it was just a natural progression for Howard to continue on and do all of the creature work from the beginning. That’s been wonderful. Howard’s my closest friend and we collaborate and write across the world, sending each other emails to see how each other is doing. It’s been great watching his stuff and our stuff develop together. A lot of the Telmarine armor got made up here in the Czech Republic and they’ve done a beautiful job on that as well. It’s been cool.

Q: Are you involved in the next movie?

Taylor: We’ve actually just started on it, we’ve been doing about four weeks of design. We’ve met the director [Michael Apted] who is a lovely guy. We’d love to be in this world for the rest of our lives if we could.

Q: It keeps a consistency…

Taylor: You’ve got to respect the fact that the audience has bought into a journey that will span most of a child’s life. If you break the consistency, you’re breaking that world. It’s interesting, a young child that entered this world on The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe would be five or six years old. They are now 9 or 10, and by the time the third one comes out they’re going to be in their mid-teens. They are on this incredible journey with these children and it’s very, very important that they grow with the kids and that the story stays consistent with the kids. I hope we get to work on them all ultimately.

Q: What kind of stuff have you had to design or work on?

Taylor: Because of the book, The Dawn Treader, it’s just that world really. It’s just really starting very initial conceptual ideas. It’s exciting.

Q: Do you ever think about stepping behind the camera? You seem to have such a good perspective on these worlds.

Taylor: You mean from a directing perspective? Um, I have been offered some directing opportunities, a fairly significant one, but no, I don’t have any interest. That’s not to undersell that opportunity; it was an incredible honor to be offered, but my heart is in the practical workshop work and anything that were to take me away from that as dumb as that may sound (laughs) is not a good way to be spent. I just love making this stuff. The morning that I left the workshop to fly out to come here, I had been working on shaping a huge castle, Miraz’s castle, and it’s so intriguing to me. We’ve been doing it for 21 years now and I’ve not found that I’ve ever abated in my interest. To take six months off away from making something to go and direct something wouldn’t appeal to me.

Taylor: You mean from a directing perspective? Um, I have been offered some directing opportunities, a fairly significant one, but no, I don’t have any interest. That’s not to undersell that opportunity; it was an incredible honor to be offered, but my heart is in the practical workshop work and anything that were to take me away from that as dumb as that may sound (laughs) is not a good way to be spent. I just love making this stuff. The morning that I left the workshop to fly out to come here, I had been working on shaping a huge castle, Miraz’s castle, and it’s so intriguing to me. We’ve been doing it for 21 years now and I’ve not found that I’ve ever abated in my interest. To take six months off away from making something to go and direct something wouldn’t appeal to me.

Q: Wouldn’t satisfy you creatively…

Taylor: No. We are developing our own product, our own children’s television and our first show’s out around the world and that gives me huge enjoyment. But as far as directing, no.

Q: Could you talk about incorporating the computers? I know you like building models and having as many real things as possible, but you also have all the things the effects departments can do. Talk about incorporating the computer stuff into things like the castle.

Taylor: You still have to composite the model into the world. The most incredible thing for a director such as Andrew or Peter or a James Cameron is that the toolbox, the repertoire of tools that exist today is so complementary of the vision that these people have. I’d like to think that there is nothing that the human mind can’t dream up now that can’t be actually realized onscreen for a sophisticated audience. You know, a seven-year-old child is a highly sophisticated moviegoer today. Therefore, that complex interplay of traditional practical techniques that have existed for a hundred years has been not superceded, but complemented by digital technology woven together into this almost evocative, spell-like visual, it’s an amazing medium. No one does it better than Andrew. We’ve just watched 15 minutes of cut together footage and you just know that he is emoting with this complex interplay of live action, digital effects, miniatures, practical, traditional… every possible tool out of that box is brought to bear to create this world. Wow, it’s just fantastic.

Q: Is there a genre you want to take a stab at that you haven’t worked in yet? I only ask because the last several years …

Taylor: Yeah, we’ve been buried in the medieval and primordial. [Even in King Kong], we were firmly stuck on Skull Island, so we were in the primordial. I love this genre, fantasy. We are getting our fair share of high science fiction at the moment. We’ve just finished a major horror movie and are doing another right now. We’ve just done 30 Days of Night and working on Daybreak at the moment. No, if I were to do fantasy for the rest of my life, I would be a very happy person. Sci-fi is an interesting medium. I like anything that gives us a challenge to build. I love children’s television, that’s where my personal heart is, that’s what we’re pursuing as our own venture.

Q: Do you guys have a relationship with the Digital FX guys? Is there a competition, camaraderie?

Taylor: Not as such, other than we have benefited hugely from the inspirational work they do, I hope it will be the same in return. A lot of the people who work at Weta have come from ILM and vice versa. The digital world, our workshop stays very consistent, the practical side of our company, and our crew fluctuates very little. Weta Digital, the digital technicians of the world, move around a little bit to go and work on premium shows so we’ve benefited hugely from the skills and abilities of the people from ILM, as has every digital effects facility in the world. They are the cornerstone of our industry. They have done much of the work that has established what we know today.

Q: I was thinking about Davy Jones from Pirates of the Caribbean and if it was maybe inspired by some of the stuff you guys did in Kong?

Taylor: I don’t know about that there. That work is cutting-edge, it’s as good as it’s ever been. It was truly the most beautiful. We were challenged with Kong because we had to evoke human emotion into a totally digital character at a level that hadn’t been achieved before but each time someone rolls on and does something so spectacular, as a moviegoer as we all are, it’s incredibly rewarding to for us to watch. I think sometimes you’re sitting in there for two and a half hours, you’ve paid your twelve dollars, you actually don’t dwell on the fact that four or five hundred, one thousand, two thousand people’s endeavors have been poured into that three hours over two and a half years. Just coming onto this set, it’s incredible. This is mobilizing of people power at an astounding level to entertain billions of people for three hours. That is a real treat that we all have been blessed with.

Q: Have you seen the castle set yet?

Taylor: No, I see it tomorrow. We’re building off of photographs and I don’t think I’ve ever seen anything like it from the photographs so I can’t wait to see it. It’s very odd being a miniature builder because you myopically focus on things. Even if you’re building a miniature as big as this room, everything you build you build on a table at scale, you bring all of the pieces together and throw into a huge miniature and it’s going to be bizarre tomorrow, having focused on the colors and tomorrow I will be walking through it.

Q: What do you think your kid will do?

Taylor: My son has just seen this twelve minutes of footage and his brain has been fried.

Q: Can you talk about the decision in this film to use Shane Rangi in the suit as Aslan. In the first film, they didn’t do that, they had a tennis ball and a head or something.

Taylor: I can’t talk to that character because I don’t know enough about that, but I think it’s fair to say, like all these things, that everyone learns. This group of filmmakers has learned some tricks from the first film, things that wouldn’t do again because it caused great pain and difficulty in post-production and then they’ve learned very sophisticated things which have really helped and allowed them to build a richer and broader world at a visual level. I think any of these techniques, I can’t speak to the specifics because I am not sure myself, but that’s why they’ll be challenging themselves… they’re fresh with it. I appreciate the level of things like hip replacement they’re doing. This is really advanced stuff. They’ve got a handheld free moving camera with a moving creature and they are digitally locking these things together in multiple plates throughout the castle. This is evoking an incredibly exciting visual world that an audience will just be blown away by. I can’t wait to see it! Even appreciating a small amount of what it takes to get it on the screen makes you realize that this is mastery at a film level that arguably may never have been seen before. That’s really phenomenal.

Q: Talk about the design motifs used for Miraz’s weaponry.

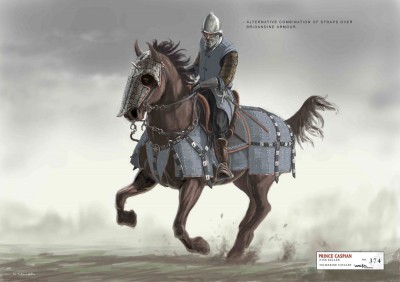

Taylor: It’s really interesting because C. S. Lewis’ world expands well beyond the literature that we know as the books of course. He drew considerably on a broad range of mythology, Grecian mythology primarily. Going forward into Prince Caspian he continued to do that. Therefore what we try and do is hang the visual motifs of the armor or the weaponry or the filigree onto certain mythological visual images. We’ve played a great deal with the creeping ivy. This is a kingless state, this is a steward that has taken hold of the land and he has promoted himself into this position, so we tried to create a visual analogy of the way that his tendrils of control have infiltrated all levels or power, government, and politics throughout the Telmarine society. We wound that through his armor, as if it’s ivy climbing over plants and strangling them. That’s how we tried to evoke that feel. But also he’s filled with incredible arrogance and pomp. Even though his armies are regal and resplendent in their armor, he still has almost taken on an almost overtly decorative quality because of his armor trying to give him grandeur. When he sheds his armor he may be quite a frail man underneath, but when he puts it on he can build up this huge personality and then he creates the idea of Andrew’s that all of his commanders can be thrown into these faceless guises by putting on these masks. It’s an absolute counterpoint to the Narnians. The Narnians are these almost feral animals now, all about their animal emotions, where the humans now guard their emotions and hide themselves under these masks. I hope that it’s successful in evoking a world in intense contrast. The world has moved on 1200 or 1300 years since we were last in Narnia and you want to give that feeling of a world in incredible turmoil.

Q: Do you have a favorite prop in this film?

Taylor: Yeah, it’s funny when we’re making props because you do fall in love with them. My favorite prop is Miraz’s buckler, the round shield fought with by Miraz. I’ve actually gone and manufactured one of my own and it sits in my office right now. I think it’s one of the most beautiful things that our crew has ever made. I was very proud of the design; it was designed by a young guy who is an incredibly talented young chap who joined up at the tail end of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. We’ve enjoyed doing all of the Miraz stuff but this one buckler was just perfectly balanced, it’s just a beautiful piece of weaponry, I’m thrilled with that. We’ve had to develop a lot of new techniques, things like the horse face plates, they look quite simple but Andrew wanted a spike out of the front of them. Now you need a firm faceplate that won’t flop and wobble around otherwise it won’t look like steel, but you run the risk of having this rigid object jamming into the flank of another horse so we’ve developed a way where we can actually blend different densities of urethane which we inject through a low-pressure injection molding gun so that the spike is soft and the faceplate is hard. It’s been really neat trying to come up with these technical chemical solutions for a fantasy/medieval movie.

Taylor: Yeah, it’s funny when we’re making props because you do fall in love with them. My favorite prop is Miraz’s buckler, the round shield fought with by Miraz. I’ve actually gone and manufactured one of my own and it sits in my office right now. I think it’s one of the most beautiful things that our crew has ever made. I was very proud of the design; it was designed by a young guy who is an incredibly talented young chap who joined up at the tail end of The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe. We’ve enjoyed doing all of the Miraz stuff but this one buckler was just perfectly balanced, it’s just a beautiful piece of weaponry, I’m thrilled with that. We’ve had to develop a lot of new techniques, things like the horse face plates, they look quite simple but Andrew wanted a spike out of the front of them. Now you need a firm faceplate that won’t flop and wobble around otherwise it won’t look like steel, but you run the risk of having this rigid object jamming into the flank of another horse so we’ve developed a way where we can actually blend different densities of urethane which we inject through a low-pressure injection molding gun so that the spike is soft and the faceplate is hard. It’s been really neat trying to come up with these technical chemical solutions for a fantasy/medieval movie.

Q: When you’re done with the stuff, is it recycled?

Taylor: They all go into very careful storage. We actually archive them and then put them into shipping containers and then put into a massive storeroom we hold. When they came to shoot the second movie, we were able to pull it all out again it was good to go. They were able to literally use the little bits they wanted to use again if they needed. We would never use it on another film because of the purity of the project but if there is a continuity of the films such as this… we were able to take some of the weapons and make them look antiquated as if they had been put in the How, locked away, and 1300 years pulled out again. They are rusted and rotted, we did a huge amount of art department work to age them and break them down. It was a huge cost savings as well.

Q: Must be a huge space.

Taylor: When you think about the cost of the real estate, but these are artifacts. Some people would say they are film props but I don’t believe that. I think they are fine artifacts worthy of looking after with great care. Whatever the cost of storage and archiving, they need to be looked after. We’ve now got 21 years of product archived with the dream that one day it can be exhibited for the world to see.

Q: What kind of material did you use to build the castle miniatures?

Taylor: The castle is such a geometric structure… it is really interesting when you build a miniature because if you look at the world of architecture even in the medieval period, the only way it stands up is because it’s absolutely pure of form. If it in any way meanders, it cannot survive. So it’s structurally incredibly solid. When you scale down, if you move that structure by even one millimeter at 24th scale, the whole thing looks like it’s wrong. So, what we did is we took the digital data from Roger’s department and we used that to drive computer-controlled hot wiring machines that cut all of the castle tower blocks out of massive blocks of polystyrene, some of which were 5 meters tall by 2 meters across. These are huge pieces of construction. Then we invented a machine, we took a cylinder of aluminum and we used a 3D milling machine to engrave and index a brick texture at 24th scale that exactly matches the 1:1 scale around the cylinder and then we built a lithographic printing press. When you turn the handle, it feeds continual sheets of 25 mill pieces of urethane through the machine and out the end you get these sheets of exact 24th scale brickwork. Then you very carefully wallpaper and then you get into all of the complex detail. We used a huge amount of 3D printing which is the technique of feeding digital data into a machine. It zips backwards and forwards and prints a three-dimensional plastic. When you melt away the support material, it will be the exact object. All the incredibly elaborate carvings around the door and so on has all been 3D-modeled and 3D-printed. We’ve used an awful lot of 3D milling technology as well to cut all of the coarse lines, all the staircases. We built the miniature of Minas Tirith which had a thousand buildings in it. It doesn’t come close to how difficult and complex replicating Roger’s full-size castle. It is so exciting and so challenging and on a monumental scale, it’s cool. I can’t wait to get it in front of the camera. We’re very fortunate that directors like Andrew still celebrate in the tradition of model-making because so many modern filmmakers are moving firmly toward digital technology as the only solution, but there’s a hundred years of history that has allowed us to get this place in filmmaking and why wouldn’t you continue to pay homage to all those techniques? Thankfully when Andrew came to these two environments, he determined that they would be built as miniatures. We consider ourselves to be extremely lucky right now.

Q: What sequences will they be used for?

Taylor: Any other shot other than the castle interior courtyard. So when the griffons are flying over, wide shots from the outside, shots flying over the walls, creatures attacking, riding across the bridge and through the town, through the trees up the sides will all be miniatures. We’re building a miniature, 100th scale, of the castle, the square of which is no bigger than this table, but it sits in a huge landscape with the rivers, the mountains, the faraway hills, the plains. The whole village is being built, the houses as big as this tape recorder, but there’s a thousand of them right down to the individually made tile roofs. It’s cool. It’s really cool.